Tough to Kill, This Pet Parasite Can Infect You, Too

More and more pets are becoming persistent carriers of this infection, and the majority of pets affected show no obvious signs. Here's the common mistake to avoid in diagnosing it, and 3 common sense precautions to help keep your home parasite-free.

STORY AT-A-GLANCE

- Recent research suggests that throughout Austria, the intestinal parasite giardia is a common cause of diarrhea in cats

- The study found that cats living in multi-cat households have a significantly higher rate of intestinal parasites

- Giardia is a root cause of many chronic gastrointestinal issues in both cats and dogs, and many cats who develop inflammatory bowel disease were giardia-positive as kittens

- A fecal ELISA or PCR test is preferable to a fecal flotation test in diagnosing giardia

Editor's Note: This article is a reprint. It was originally published December 03, 2015.

A recent study conducted at the Institute for Parasitology at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna, Austria revealed that the intestinal parasite giardia is a common cause of feline infections and diarrhea.1

The researchers tested 298 feline fecal samples for single-cell intestinal parasites, also called enteric protozoa. The samples were taken from cats throughout Austria, including animals living in private homes, catteries, and shelters.

Of the 298 samples tested, 56 were positive for at least one intestinal parasite. One species of giardia the parasitologists found may be zoonotic, meaning it is transmissible to humans.

The researchers discovered that a significantly higher rate of positive fecal samples came from multi-cat households. Kittens are also at greater risk. According to Barbara Hinney, lead study author:

"Young animals must first come to terms with the pathogen and are not yet immune, which makes it possible for the pathogen to persist more stubbornly. When the animals excrete the parasite via feces, they infect other cats. This gives households with more than one cat a higher risk of infection."

In addition to giardia, the parasitologists also found a variety of other intestinal parasites, including:

- 1.7% of fecal samples were positive for cryptosporidium

- 4% contained cystoisospora

- 0.3% contained sarcocystis

- 2.5% were positive for Tritrichomonas blagburni

Giardia Was Found To Be the Most Common Intestinal Parasite in Cats in Austria

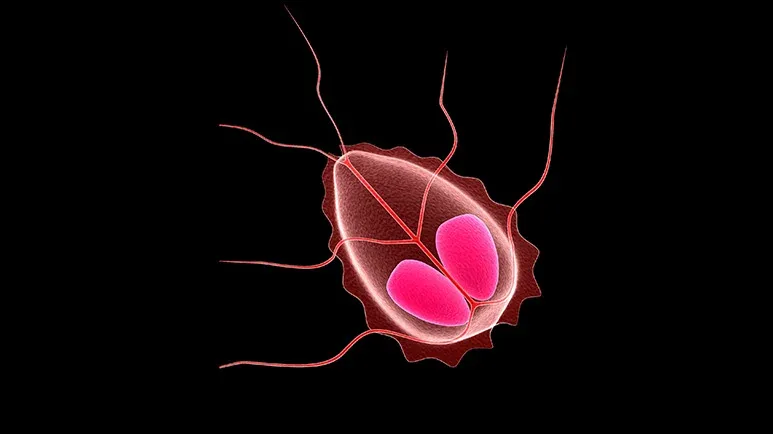

Giardia infections were found in over 12% of the fecal samples. The giardia parasites are ingested as cysts, and invade the small intestine where they reproduce. The cysts then re-enter the environment in infected cat poop.

Most of the giardia species the researchers found occur only in kitties, but one species also exists in humans. However, "Most human giardia infections occur through human-to-human transmission," says Hinney.

Giardia infections can be very difficult to cure, and recurrence is possible even after successful treatment. Giardia cysts can survive for long periods in warm, moist environments.

The researchers recommend that catteries wash cat blankets and towels at 140 degrees F, and clean bowls and food dishes regularly with hot water. Also, since giardia can be transmitted in water, cat feces should never be disposed of in the toilet.

Giardia Is the Root Cause of Many Chronic GI Issues

Giardiasis is actually much more common in dogs than cats, but if your kitty spends time outside and comes in contact with the poop of an infected animal or contaminated water, it's a possibility.

Many people don't realize that giardia is pervasive in the environment. Scientists don't know a lot about this one-celled organism. We do know it is frequently found in dogs, cats, most wild animals, and even in many people living in third world countries.

In my experience, the giardia parasite is the root cause of many cases of chronic GI inflammation in cats (and also dogs). Many of the kitties referred to me for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were also giardia-positive as kittens.

And many referrals for chronic GI issues like persistent diarrhea or malabsorption also test positive for giardia.

Exposure and Transmission

While exposure to giardia is common, acquiring disease from the parasite is less common.

Your kitty can be exposed to giardia by ingesting an infected cyst lurking in another animal's feces. Contamination occurs either directly or indirectly through contact with infected cysts.

Many kittens are exposed to giardia very early from parasite positive mothers and may be harboring these parasites asymptomatically at the time they are adopted.

Once a giardia cyst makes its way to your cat's small intestine, it opens to release the active form of the parasite. These organisms have the ability to move around and attach to the walls of the intestine, where they reproduce.

Eventually, the active forms of the parasite encase themselves in cysts and pass from the cat's body in feces. The infected poop then contaminates water sources, grass, soil, and other surfaces.

Another way transmission can occur is if a cat cleans her bottom and then licks another cat.

Symptoms of Giardiasis

The majority of pets with giardia show no obvious signs of infection. For those kitties who do experience symptoms, the most common is diarrhea that can be acute, chronic, or on-and-off.

When diarrhea from a giardia infection comes and goes, often, pet parents write off the occasional loose stool to indiscriminate eating or a random food sensitivity.

This is why so many cases of giardia go undiagnosed — sometimes for months or even years. Eventually, a cat with a long-standing giardia infection can suffer a severe, debilitating episode of bloody diarrhea that causes dehydration.

Most of these kitties don't lose their appetite, but they often do lose a noticeable amount of weight. This is because the parasitic infection in the GI tract is interfering with digestion and absorption of nutrients from the food they eat.

Diagnosing Giardia

The giardia parasite is microscopic and can't be seen with the naked eye. Unfortunately, parasite testing performed at your veterinarian's office instead of an independent laboratory may not be accurate. Estimates are that up to 30% of in-house tests return a false negative, which means there are a lot of giardia-positive animals testing negative for the infection.

National veterinary labs like Antech and Idexx use standardized equipment that returns consistently reliable results, so if you're having your pet tested for giardia, I recommend asking your vet to send the samples out for analysis.

Another challenge in diagnosing giardia is that the parasite isn't shed in every stool. This means there can be cyst-free stool samples from infected animals. If one of these samples happens to be the one collected for analysis, it won't show any evidence of giardia, even though the kitty is infected.

I recommend an ELISA or PCR test for giardia for any pet with a history of GI issues. A fecal ELISA or PCR test is preferable to a fecal flotation test because it checks for the presence of giardia antigens. A fecal float only detects giardia cysts, which may or may not be in the particular stool sample being tested.

Unfortunately, many vets don't routinely run the ELISA or PCR test and instead, use only stool sample results that may or may not pick up evidence of infection. So make sure to ask your vet for a fecal antigen test in addition to a fecal float.

Labs now offer "diarrhea panels," which check for other common causes of diarrhea and this is an excellent diagnostic choice for any cat with intermittent GI issues.

Treating a Giardia Infection

The giardia parasite is becoming resistant to many anti-protozoal drugs, which means more and more pets are becoming persistent carriers of the infection.

What I do in my practice is run monthly fecal float tests for three to four months after completion of treatment, sometimes followed by an ELISA test to make sure the infection is fully resolved. The ELISA test can be giardia-positive for up to six months after treatment, because it takes awhile for the antigens to clear out of the bloodstream. This is why I don't run them immediately after treatment completion.

A few fecal floats will give you and your vet the most accurate information about whether the infection has been successfully treated. The reason for more than one test is, again, because giardia cysts aren't passed in every stool, so a test immediately following treatment may be negative, but a test a week later could be positive. If you stop after one fecal float, it's very difficult to be absolutely sure the infection is gone. To prevent a giardia infection in your cat, take a few common sense precautions:

- Don't house your pet in close quarters with other potentially infected animals

- Clean up your cat's poop outdoors, and don't allow him access to areas where other animals relieve themselves

- Don't allow your cat to drink from outdoor water sources