Why Your Pet Seems Just Fine Eating Any Food

Taught by animals and their owners, this world-renowned animal nutritionist exposes the 900-pound gorilla sitting in many pet food bowls. Find out why the most economical - and most popular - approach to feeding pets may appear to meet your pet's needs today but implode on you later.

STORY AT-A-GLANCE

- Dr. Richard Patton, a favorite nutritionist of the fresh feeding community, believes that “nutrition is never a crisis” — but it can lead to one over time

- The “900-pound gorilla in the room” when it comes to processed pet food is excessive levels of soluble carbohydrates

- The primordial diet of dogs and cats, which evolved from the wild world, contained very little in the way of soluble carbs; discarding it will naturally have consequences

- No one, including AAFCO, is measuring the lifetime nutritional adequacy of commercial pet food

Editor's Note: This article is a reprint. It was originally published September 22, 2019.

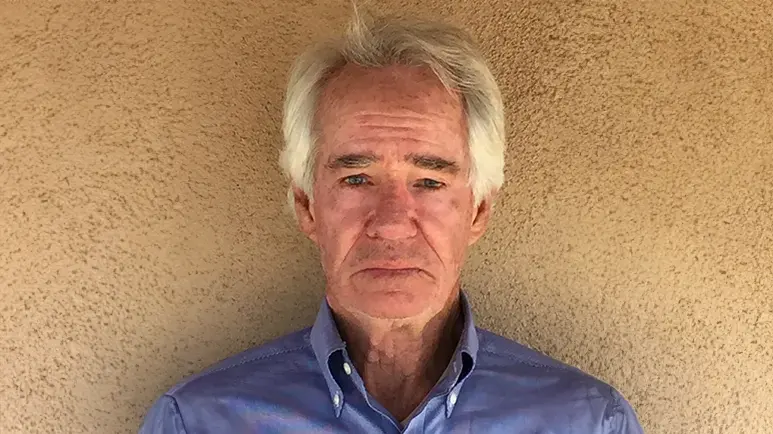

Today, my very special guest is Dr. Richard Patton, a world-renowned animal nutritionist. Dr. Patton's career, which spans several decades, has been dedicated to helping animals eat better food. He has formulated diets not just for dogs and cats, but also zoo animals, including wild carnivores.

"I'm probably the oldest surviving animal nutrition consultant in captivity," jokes Dr. Patton, "I've been a nutrition consultant for 40 years. I have worked in about 27 different countries. Much of my career has been making diets for zoo animals. I've developed a certain perspective — you might call it comparative animal nutrition — which has given me a great deal of insight into the subject.

Hopefully, all my years of experience give me something of value to contribute. We all want to do what is best for each animal and the humans caring for that animal. That's my ambition when I get up every day."

Nutrition Is Never a Crisis

One of Dr. Patton's very thought-provoking and long-standing perspectives is that "nutrition is never a crisis." When an animal isn't eating the right food over a period of time, his health gradually deteriorates until it becomes a crisis. And since veterinarians are trained primarily to deal with health crises, when nutrition finally creates one, it provides the stimulus they require to take action.

"The truth of the matter," explains Dr. Patton, "is that an animal who presents with a crisis at the veterinary clinic may have been eating inadequate nutrition for months or years. It's because of the exquisite adaptability that evolution has built into everything, that the diets we feed animals can seem to work — for a while."

Dr. Patton is absolutely right, and I talk about this all the time as well — veterinarians aren't trained to, and therefore do not look at what animals are fed as a potential contributing factor to the many chronic degenerative diseases plaguing pets today. Something else we're not taught is that an obese pet can be profoundly nutritionally deficient. Overfat and undernourished is a common issue with pets throughout North America today, and Dr. Patton covers this a lot in his writing and lectures.

"It's the 900-pound gorilla in the room," agrees Dr. Patton. "The problem is the excessive amount of soluble carbohydrates in the average pet diet, and the culprit is kibble. As in human nutrition, trendy pet foods come and go, but most of them are just variations on a single theme, which is lowering the amount of soluble carbohydrates. It benefits all animals, including humans."

The Problem With Kibble: Excessive Amounts of Soluble Carbs

I'm often accused of being a kibble-basher. I honestly don't want to be anti-kibble, but the truth is, providing highly processed, shelf stable pellets as the sole source of nutrition for any animal may not be ideal:

"It's all about perspective," Dr. Patton says. "A bag of potato chips and a soda will get you to the next day just fine, but we all know that a lifetime of eating that diet will be shorter than it should be. Again, the adaptability of animals allows us to feed them a bad diet for a while and they seem to get along okay.

The use of excessive amounts of soluble carbs, which is a failing of kibble, needs to be addressed. I'm not wholly against kibble, either. The kibble industry is getting better at lowering carbohydrate levels. There was a time when 50% of most commercial kibble consisted of soluble carbohydrates.

But processed pet food manufacturers aren't stupid. They didn't get to be the behemoth industry they are today by making bad decisions. They're aware that soluble carb levels are a discussion point among professionals.

They're doing what they can to lower them, and I commend them for that. But they're not there yet. I mean, there's one brand that claims to be 23% or 25% soluble carbs, but they're fudging the numbers. If you do the math correctly, they're closer to 30%, but 30% is an improvement from 50%. They're moving in the right direction.

The point is that the primordial diet, which evolved from the wild world that was the operating stage for the evolution of everything for billions of years, contained very little in the way of soluble carbs. Nature made it very hard to find soluble carbohydrates, and animals adapted to that reality. Then humans came along and made soluble carbohydrates very easy to find, and today we're all consuming too much."

And, I'll add, they taste delicious, they're cheap, easy to find, and highly addictive. It's easy to feed them to animals, who also often think they taste delicious, and assume there's no issue. But from a nutritional standpoint, soluble carbs are far from ideal in the long-term. They're not ideal for us, and certainly not for carnivorous cats and dogs.

Discarding Cats' and Dogs' Primordial Diets Has Consequences

Our next topic of discussion is dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), which is now a concern for dog parents and veterinarians everywhere as the canine case count climbs. As I'm sure almost all of you listening or reading here are aware, the current mini-epidemic of DCM in dogs has been linked to both a taurine deficiency and grain-free kibble diets, but there's still a long way to go in understanding cause and effect.

Dr. Patton has been an expert on this subject since the 1970s when we learned that a taurine deficiency was causing DCM in cats. Since then, taurine has been supplemented in commercial cat food, but I fear that by only addressing one amino acid deficiency, we've put a Band-Aid on a gushing wound we can't yet see.

"I would concur," Dr. Patton says. "We're putting a Band-Aid on a blister when what's really needed is to change shoes. I've been through different iterations of this discussion, beginning with the work at University of California at Davis back in the '70s that showed cats had an issue with taurine.

But we must keep this in perspective. Cats can't make taurine, but in their primordial setting, they didn't need to. They were exquisite hunters. They always had fresh meat and therefore, adequate taurine.

Dogs supposedly can make taurine, and we tend to think this is because they're evolutionarily advanced compared to cats. That's not necessarily so. Because dogs were poor predators compared to cats, evolution presented them with a mutation to make taurine. This was necessary because the dog didn't get enough taurine as a predator.

But you see, making your own taurine comes at a cost. The process uses cysteine, and the body has lots of other uses for cysteine besides making taurine. Cats don't need taurine if they eat the right diet — their primordial diet — because they're getting plenty of meat and therefore, plenty of taurine.

So, what the researchers at UC Davis showed us back in the '70s is that if you take a cat off his all-meat diet and give him grains, he becomes deficient in taurine and you have to supplement. The pet food industry and its marketers and advertisers got wind of this, so today what we have is a lot of finger-pointing and name-calling in the marketplace.

As in, 'Look! We have taurine and they don't! We're better than them. Buy our brand.' But the fact of the matter is if you have to add taurine to make the diet nutritionally adequate, it wasn't a naturally balanced diet to begin with.

Now, we come to the dog. It seems as if the enlarged heart (DCM) discussion came out of nowhere, and now we're all doing the Chicken Little drill, running around yelling, 'The sky is falling! The sky is falling!' But if we backtrack and take a more careful look, I think we'll learn the problem has probably been brewing for quite a while."

Dr. Patton also points out the need to keep the actual number of DCM cases occurring in dogs in proper perspective. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported 519 cases over the past year and a half. So, out of 120 million pets in the U.S., there have been 519 reported cases of DCM in the past year and a half. His point is that we need to avoid panicking, continue to gather as much information as we can, and try to understand what's happening.

No One Knows the Nutritional Adequacy of Processed Diets

The vast majority of pet owners are feeding highly processed diets, and while I'm thankful that many manufacturers are trying to reduce the number of synthetic vitamins and minerals in their formulas, I think they tend to discount the impact of processing techniques (e.g., extrusion) on the nutritional value of their products. How does extruded food affect the microbiome, amino acid digestibility, and digestion and absorption of other nutrients?

No one is studying that because AAFCO feeding trials don't measure those things and run for just six months. I asked Dr. Patton for his views on AAFCO feeding trials as the "gold standard" for the industry.

"I think your points are valid," Dr. Patton replies. "How well do their feeding trials really define a diet as adequate pet nutrition? I have the same question. And I have an additional argument. Let's say you have a dog food for which you want an AAFCO approval rating for 'all life stages' and you're willing to do the feeding trials.

These types of feeding trials result in the production of something like 100 puppies for no other reason than as use as 'lab rats' for your project. I think this is highly irresponsible. I want no part of it.

None of my clients do AAFCO feeding trials of any kind for 'all life stages.' They do 'maintenance' trials involving existing animals, and we end up with more insight on those diets than if we didn't do the trials. But do we have enough information to say, 'You're good to go forevermore because you lasted six months on the diet?' No, we do not."

Most importantly, to my way of thinking, is that feeding trials don't measure anything pertaining to nutrition. There's no measurement of antioxidant status, or how long the food will maintain its nutrition once opened. The trials aren't designed to measure a food's effect on the microbiome, its digestibility or its absorbability. All they measure is whether the food keeps six of eight dogs alive for six months.

I think the deficiencies in AAFCO feeding trials may be part of the reason we're seeing some of these emerging nutrition-related diseases, like DCM. We're not actually measuring how nutritious a food is over a pet's lifetime.

How Can We Help People Feed Their Pets Right for a Lifetime?

Next I asked Dr. Patton for his thoughts on using synthetic nutrients when formulating pet diets. I don't like to use them, but it's hard to avoid them completely, especially when it comes to hard-to-source nutrients, such as zinc and vitamin E.

"When it comes to synthetic vitamin E," says Dr. Patton, "the people who make it think they have adequate proof that it's as bioavailable as natural vitamin E. After years of battling with them, we finally got them to admit it's not as good as natural vitamin E, but it costs much less, so just feed more. They take a negative and turn it into a positive for them. They sell more.

There's a continuing piling on of these kinds of issues. For example, AAFCO mandates 100 parts per million zinc. I have to really shake my head at this one. Having made diets for animals of all kinds all over the world for decades, that 100 parts per million standard is four times the zinc requirement of any creature I've ever encountered.

I think that for a state department of agriculture to be legally allowed to red tag an entire production of a pet food because it has 80 parts per million zinc instead of 100 is a complete loss of perspective.

Somewhere between what nature offers, which is the perfect nutrition — animals thrive in the wild — and the other extreme, which is kibble from the grocery store, we must find a happy medium. How do we move forward in the midst of all this turmoil and confusion? What advice can we offer to help as many pets as we can, and harm as few as possible?"

I asked Dr. Patton if he believes the time is coming when veterinary professionals will be willing to consider the idea of rethinking what constitutes optimal nutritional requirements for dogs and cats.

"With all due respect to AAFCO," Dr. Patton replies, "I think we're headed unequivocally toward abandoning the entire AAFCO approach, leaving it like a ghost ship afloat on the open sea. AAFCO can say what they want, mandate what they want and play word games such as, 'We don't do enforcement. We let the state departments of agriculture enforce.' They're passing the buck and people are getting fed up with it."

Dr. Patton and I both receive lots of heartbreaking questions from pet parents along the lines of, "Our 14-year-old Labrador was just diagnosed with cancer. What should we be feeding?"

"I obviously never say this in real time in response to those questions," says Dr. Patton, "but what I always try to emphasize in general is, the time to ask that question was 14 years ago. Let's get that pup weaned on mother's milk, get her launched, and then let's feed her correctly for the rest of her life. She'll be your family member for 15 or 18 years, so let's get her fed right."

We Need to Address the 900-Pound Gorilla in the Room

I asked Dr. Patton, if he were passing the torch to a new generation of animal nutritionists, what he would advise them to focus on first among all the problems with commercial pet food.

"I think the excess soluble carbohydrates issue is the biggest problem of the moment," he replies. "All the others can wait. I'll attack them when we get this 900-pound gorilla out of the room. Worrying about zinc levels, by comparison, is like the proverbial 'rearranging the deck furniture on the Titanic.' There's this much larger concern that I am completely preoccupied with.

Now, to use your words, which I so love, 'What do I want the world to know?' Here's something I'm always so aware of. Despite formal training as an animal nutritionist, just about everything I know of any real value was taught to me by animals and the owners of animals. I only advise the pet owner to be sure and listen to their pet.

When they have a bowel movement and you're looking at their feces, you want it to be a cigar that you can kick across a shag rug. If they're squirting puddles, this isn't necessarily bad, but it's a red flag. You want to be sure and listen to what your pet is telling you.

If they're eating feces, I'll ask, "Is it horse feces or is it their own?" There's a big difference. Most creatures will eat feces of other species, but if they're eating their own, this is a different message. Are they eating grass? Is it just so that they can vomit? Okay. That's one thing. Are they eating grass on a more consistent basis? Be sure to see what the pet is doing and hear what they're doing and listen."

If you want to calculate how much carbohydrate is in your pet's food, you'll have to do some basic math, but it's worth knowing how much unnecessary filler (that may be potentiating disease) is in your pet's bowl. Next, I asked Dr. Patton if he has changed the way he feeds his own dogs over the years.

"Early on in my career, I drank the Kool-Aid," he explains. "I think we all do this with the best of intentions. But you have to be open-minded and humble, realizing you may not have all the information you need, and you may not be making the best decisions. Stay open-minded and recognize that the truth can come from anywhere, including, God help us, a veterinarian!

And be willing to connect the dots. For example, back on my rant about soluble carbohydrates and the fact that there are none in nature, enlarged hearts were not a problem in dogs until just recently. What have we been doing to dogs diet-wise for the last 50 years? I keep coming back to the same answer. All this starch and sugar is not doing anybody any good."

Dr. Patton feeds a fresh meat diet to his dogs and is one of only a few animal nutritionists who advocates biologically appropriate foods in recognition that dogs and cats do best eating a very low-carb, meat-based diet.

"I believe that probably God and St. Peter were most exasperated with me at the very beginning that I couldn't seem to learn my lessons," says Dr. Patton. "One of the very first things I accomplished as an animal nutritionist was to be part of a group that formulated an all-natural diet for tigers in captivity.

It was wildly successful, and we set a world-record of six cubs born in captivity. And those same tiger parents went on to set another world record on that diet — 36 cubs total born in captivity. That same team at the very beginning of my career was responsible for the first golden eagle chick born and raised in captivity eating a natural diet.

So, from the beginning, the seeds were planted in my thinking, but then I went on to work for big kibble and practiced the dietary management of disease from the veterinary perspective. All along the way, though, I gained more insight. There was once a time when I would have said, 'Natural's not good.' But if you told me the day would come that I would say 'Natural is a better way to go,' I would have called you a liar back then."

The Future of Fresh Pet Food

Speaking for the fresh-feeding community as a whole, I really appreciate all that Dr. Patton is doing to help facilitate a bigger, broader conversation than the one most nutritionists are willing to have.

"My approach doesn't abandon science at any point," Dr. Patton adds. "I think a competent investigator doesn't dismiss counterpoints. What I say is, 'Show me your data.' I'm not going to say to somebody, 'You're wrong. I'm right.' I'm going to say to them, 'Show me your data, because I think mine's better. I think soluble carbs are causing us problems, along with other things. I want that fixed'."

When it comes to the cost of feeding real food to pets and its effect on consumer demand, Dr. Patton says:

"The fastest growing segment in the pet food community is freeze-dried raw. I like what this is saying. But it's still a tiny sliver of an absolute behemoth industry. We're just going to have to keep playing our tune and making converts as best we can when we can.

I think as more pets move from living in the backyard to being members of the family, people are going to tend to forsake their economy-first approach to nourishing their family members. Their willingness to feed proper nutrition is going to gain traction and sticker shock will be less of an issue."

I agree, and I also think that over time, as more competition enters the fresh pet food marketplace, prices will start to trend downward. It's been a sincere pleasure to chat with Dr. Richard Patton today and get his insights and thoughts on how we can better feed the animals we care for. I appreciate all he's done and continues to do for the fresh pet food industry and for taking time to talk to us today.